When I was around eleven or twelve, I was old enough to understand the inevitability of death but young enough that I still prayed. I remember telling God that I knew he would someday have to take my grandparents to heaven, but I asked that he please not do so until I was old enough to handle it emotionally. I thought about how old I would have to be in order to bear the burden of grief, and I settled on asking God to wait until I was in college. By the time I was in university, I figured, I would have the emotional tenacity to handle the death of a grandparent.

My mother’s mother, Joan, or Grams, as I knew her, passed away on December 23rd, Christmas Eve Eve. She loved hummingbirds and ice skating, rivers and rocks, the smell of lavender. I’m 25, three years out of college, and I’m not handling it well.

It almost feels silly. I cry to the point that my mom must comfort me, meanwhile I’ve suffered a far less traumatic loss than her. Then sometimes I remember that my tendency toward outward displays of emotion come directly from my Grams, who would often start off Thanksgiving grace by thanking God “for family” through grateful sobs. This reminder, of course, only makes me cry harder.

When the lockdowns began in March, I saw a post online in which someone complained that he was going out of business just to prevent “a few old people from dying.” While I would love to consider this the thoughtless comment of an upset outlier, I, unfortunately, believe that he represents a large population of people. A lot of folks during this pandemic have lost their entire social lives, their jobs, new relationships, and worse, due to  quarantine, and it can be a tough sell to justify those losses as necessary to protect the elderly. As a result, many have made the morbid decision to argue that it simply isn’t worth it. The obituaries in my hometown grew thick as Covid rattled through the nursing homes. Many young people jokingly called the virus “the boomer remover.” This attitude communicates dryly that, while it’s not ideal, old people dying is not a tragedy.

quarantine, and it can be a tough sell to justify those losses as necessary to protect the elderly. As a result, many have made the morbid decision to argue that it simply isn’t worth it. The obituaries in my hometown grew thick as Covid rattled through the nursing homes. Many young people jokingly called the virus “the boomer remover.” This attitude communicates dryly that, while it’s not ideal, old people dying is not a tragedy.

My grandma’s death was not related to Covid, but it was in this emotionally distanced environment that we lost her, and the circumstances cause me to feel guilty or shameful about how fiercely I’ve been shaken by grief. It almost feels unjustified to cry over someone whom many deemed disposable.

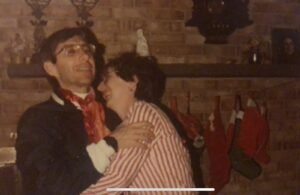

But, of course, to us, Joan wasn’t a theoretical scapegoat or an anonymous old lady. Sure, she was an old lady when she died, but in our memories, she isn’t exclusively an ailing senior. To those of us who gathered around old videotapes on the day of her funeral, she’s a 21-year-old asking her friend to record her climbing a tree by standing on an open garbage can and reaching for the branches. To my grandfather, she was four years younger than him, so he teased her, calling her school a kindergarten. To my mom and her siblings, she’s a young mother who would put the kids to bed then ice skate on a temporary rink that my grandfather set up in the backyard for her. Even through her 40s and 50s, she was in the newspaper for her advocacy to clean up the Potomac River and its tributaries, speaking passionately on the subject on her radio show, and living on a canoe for weeks to raise awareness of pollution. To me, she was a large collection of flowery hats, framed poetry, the smell of sunscreen, the woman who would bounce me on her knee and work her way through a seemingly unending repertoire of silly songs. So many versions of her in our scattered memories don’t portray someone past her due date, but rather a vivid character who loved being alive. Wouldn’t losing that person be a tragedy?

To my mom and her siblings, she’s a young mother who would put the kids to bed then ice skate on a temporary rink that my grandfather set up in the backyard for her. Even through her 40s and 50s, she was in the newspaper for her advocacy to clean up the Potomac River and its tributaries, speaking passionately on the subject on her radio show, and living on a canoe for weeks to raise awareness of pollution. To me, she was a large collection of flowery hats, framed poetry, the smell of sunscreen, the woman who would bounce me on her knee and work her way through a seemingly unending repertoire of silly songs. So many versions of her in our scattered memories don’t portray someone past her due date, but rather a vivid character who loved being alive. Wouldn’t losing that person be a tragedy?

When a friend asked how I was doing after my Grams’ death I said, trying to sound tougher than I truthfully am, “You know, she was old, and she was dying for a few years. It’s sad, but it’s not a tragedy.” I did, however, betray myself later in the conversation by choking up over simple stories about her. And while there is some truth in the idea that there are times to let go and make room for the new, I was wrong to ever say that her death wasn’t tragic. Because it was. Losing anyone you love is a tragedy. Even if they were sick. Even if you’re a grown adult. Even if they died a long time ago. Even if they were old. Grief ebbs and flows without warning, and there is no explaining it or apologizing for it.

When a friend asked how I was doing after my Grams’ death I said, trying to sound tougher than I truthfully am, “You know, she was old, and she was dying for a few years. It’s sad, but it’s not a tragedy.” I did, however, betray myself later in the conversation by choking up over simple stories about her. And while there is some truth in the idea that there are times to let go and make room for the new, I was wrong to ever say that her death wasn’t tragic. Because it was. Losing anyone you love is a tragedy. Even if they were sick. Even if you’re a grown adult. Even if they died a long time ago. Even if they were old. Grief ebbs and flows without warning, and there is no explaining it or apologizing for it.

The last time I saw my grandmother she was standing in her doorway with my grandfather. We were all wearing masks, and we did not touch or hug through the entirety of the brief visit. I had been out of the country and I hadn’t seen them in person for three years. My siblings had not seen them since the beginning of quarantine, and there was much debate in my household over whether or not it was worth the risk to visit. But I wanted to introduce my grandparents to my partner and give them some cookies I had brought from Argentina, so we promised to be safe and made a stop at their house outside of DC.

“Won’t you please come in?” She kept asking me, confused.

“It’s not safe,” I explained, “And we have to be careful. You’re too important.”

And when her dementia caused her to forget why we couldn’t come inside, and she invited us again, I gladly repeated, “You’re too important. You’re too important.”