On March 27th, The Cut published an essay called “The Case for Marrying an Older Man” by Grazie Sophia Christie. In the essay, the writer explains that she realized in undergrad at Harvard that her “fiercest advantage” as a woman was her youth. She argues that she leveraged her youth to seduce and marry an older French man despite her relationship being highly criticized by her friends and her husband’s female colleagues. But now, Christie claims to enjoy a life of leisure with her husband. His wealth and seniority gave her the opportunity to quit her job and pursue writing full-time. She compares her own lifestyle to that of her female peers who have “partners,” which she defines as boyfriends who are men their age, who, she claims, don’t do their part, which leaves her friends in unfulfilling and unequal romantic relationships. She does mention the pitfalls of her marriage; for example, she feels very dependent on her husband and wonders how much of her identity comes solely from him. But she criticizes feminism for not offering her something that her older husband did offer her: ease.

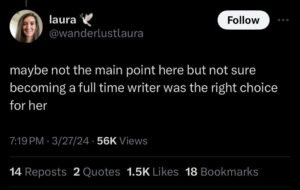

The essay was heavily criticized. But readers didn’t just call this woman misogynistic.

They called her a bad writer.

I would predict that Christie will dismiss these bad-writer allegations as jealousy or ad hominem attacks from people who disagree with her personal take and are trying to hit her where it hurts. In many cases, I think she would be right to do so.

So, in this response, I’m not going to discuss Christie’s personal choices or opinions—she’s entitled to them—but I am interested in answering the following questions: Is the writing bad? If so, why? How would I fix it?

My name is Siobhan Brier Aguilar, I’m a professional writer, editor, and translator at Inkless Writing Agency.

In my opinion, the principal problem with this essay is that it was framed as an opinion piece, but it had the voice and writing style of a novel. I think that, best case scenario, this piece would’ve been placed behind a thin veil of fiction and presented as a short story, and if the writer really wanted to talk about her own life, she could have written it as a personal essay without a thesis, saying, “this worked for me,” without explicitly recommending her lifestyle as a salve for… labor.

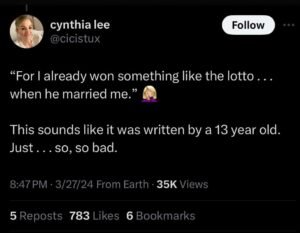

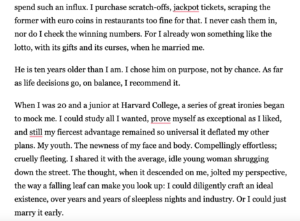

Instead, the first two paragraphs give us a very clear thesis. She says:

“In the summer, in the south of France, my husband and I like to play, rather badly, the lottery. We take long, scorching walks to the village — gratuitous beauty, gratuitous heat — kicking up dust and languid debates over how we’d spend such an influx. I purchase scratch-offs, jackpot tickets, scraping the former with euro coins in restaurants too fine for that. I never cash them in, nor do I check the winning numbers. For I already won something like the lotto, with its gifts and its curses, when he married me.

He is ten years older than I am. I chose him on purpose, not by chance. As far as life decisions go, on balance, I recommend it.”

Now, I should mention again that this was published in The Cut. A lot of these publications that aren’t behind a paywall and get most of their readership online need clicks and traffic to stay afloat. A good way to get clicks is through polemic headlines, and if this were a personal essay, it probably wouldn’t have gotten so much engagement. So, in that sense, this was a successful essay; a good essay.

Still, I feel that the initial structural choice to make this an opinion piece led to other issues with the essay. For example, one reader said:

Which is a take, I disagree with, but I understand where they’re coming from. This reader was expecting a sort of op-ed, and instead they got a portion of a memoir in an op-ed costume. An opinion piece, as opposed to a personal essay, has less leeway in terms of breaking grammar rules. But this writer is a novelist. Fiction, and even personal essays, can break grammatical and structural “laws” and still be good, so long as the rules are broken deliberately and serve a greater goal, such as the voice of the piece, the tone, the plot, the character, etc. With a poetic license, you can do things “wrong,” so long as it’s a choice. A choice that you can justify. So then, the question becomes less about whether or not a rule was broken, and more about the intentionality of breaking that rule.

So let’s not rescind her poetic license just yet.

The Grammar

Now, we’ll do a line edit and see if we can clean up some grammatical errors without sacrificing the writer’s voice, because she does this sort of whimsical, romantic, musical tone that really works in some instances.

Misplaced Commas

Grammarly doesn’t love the way she uses commas, but I’m honestly not always concerned about that. Sometimes, writers intentionally place or don’t place commas in order to direct the pacing of the piece and tell you where to take a slight breath or stop to absorb something you just read, and personally, I think she does that effectively. If you overuse Grammarly or if you’re really a stickler for grammar rules, then sometimes it can make the writing come across as stale or ChatGPT-sounding. So as an editor, I would actually leave most of those in.

Relative Pronouns

There are some grammar mistakes that I would take out. For example, we’re having issues with relative pronouns.

“There is no brand of feminism which achieved female rest.”

Here, we should say “that” instead of “which.” The difference between the two is that “that” introduces a relative clause that is necessary to the meaning of the sentence, and “which” introduces a relative clause that wouldn’t change the meaning of the sentence if it were taken out. In this example, if we took out the relative clause, the sentence would just say, “There is no brand of feminism,” which has a completely different meaning. That tells us that the relative clause is restrictive, so it should read, “There is no brand of feminism that achieved female rest.”

There are a few sentences that confuse that and which, and there is one sentence that says, “I live in an apartment whose rent he pays, and that shapes the freedom with which I can ever be angry with him.” If we were intentionally personifying the apartment, that is, talking about the apartment, an inanimate object, as if it were a person, then saying an apartment “whose” would be permissible, but we aren’t, so it would better read as: “an apartment where he pays rent.”

Unclear Antecedents

There are also a few cases of unclear antecedents; for example, she wrote: “What was I doing, in marrying older, if not endorsing it? I had taken advantage of their disadvantage. I had preempted my own.” In that sentence, it’s unclear if by, “my own,” she means her own advantage or her own disadvantage. And sometimes the piece does perhaps lean too much into an airy quality in the writing and unintentionally sacrifices clarity— not ideal for an opinion essay when you have a thesis you’re trying to prove.

Allusions

Something else I would change about this essay is some of the references. I, personally, love references to classic literature or any other major work when they are done well. I like feeling like the author is teaching me about something, and, even when I’m just reading something entertaining, I can get these little golden nuggets of knowledge. References in a persuasive essay can also lend the writer a lot of “ethos,” which is a rhetorical technique that uses the personal authority of the speaker as a means to persuade the audience. A well-done allusion to another work of art can tell me subtly that the author has done their research and knows what they are talking about.

But when those references are overdone or unnecessary, they can have the opposite effect, and instead come across as forced, like the author is trying to overcompensate. In James Scott Bell’s “The Art of War for Writers,” Bell claims that one of the immediate signs of an inexperienced writer is someone who hits you over the head with their research. It comes across as: “Look at how much I know! Look at how much research I did!” And it pulls us out of the flow of the writing, which is counterproductive to making a point or telling a story.

So let’s look at Christie’s allusions.

“I could not understand why my female classmates did not join me, given their intelligence… Perhaps it came easier to avoid the topic wholesale than to accept that women really do have a tragically short window of power, and reason enough to take advantage of that fact while they can. As for me, I liked history, Victorian novels, knew of imminent female pitfalls from all the books I’d read: vampiric boyfriends; labor, at the office and in the hospital, expected simultaneously; a decline in status as we aged, like a looming eclipse.”

Firstly, the implication that the only reason that other women her age weren’t seeking out older, wealthier partners is because they are either in denial or don’t know enough about history and Victorian novels is, incredibly condescending. Secondly, I don’t buy that she started to worry about her status and biological clock because she read Victorian novels. Many of her gripes about feminism, or even just being a woman that we see in the rest of this essay are pretty clearly modern and often Internet-influenced, which is fine, but we should be honest about our sources to build credibility and trust with our audience. Later in the essay, she writes, “I find a post on Reddit where five thousand men try to define ‘a woman’s touch,’” which comes across as a more genuine influence in her way of thinking as opposed to Victorian novels.

But let’s put my English degree to good use and explain those references she made. She says that in reading Victorian novels, she finds cases of “vampiric boyfriends,” which sounds, to me, like a reference to Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte. Heathcliff is a really complex, interesting character who loves Catherine Earnshaw but is also jealous and cruel and vampiric toward her and her family.

“Labor, at the office and in the hospital;” I can’t think of a direct comparison to that, but it could be Middlemarch. In Middlemarch by George Eliot, the character Dorothea Brooke marries an older, wealthy man but she feels stifled by the relationship and later seeks out volunteer work at a hospital and gets more fulfillment out of that. But I think it would be a strange choice to include this reference in an essay about the benefits of marrying an older man, because Dorothea Brooke was severely controlled and unhappy in her marriage to an older man and she didn’t get her happy ending until her older husband died and she married a bright, revolutionary, starving artist, who was her age. So, if you can think of a different Victorian novel that has a woman who has to work in an office and a hospital (or maybe she meant domestically and in a hospital?), then leave a comment. Either way, if I were the editor for this piece, I would ask the author what she meant by this and why she chose it.

The “decline in status as we age, like a looming eclipse” line makes me think of Vanity Fair. That could be House of Mirth. Victorian novels talk a lot about status and wealth, you know, Victorian England was really stratified, so this tie between Victorian literature and a woman’s decline in status; I think it works better than the other allusions.

Another reference that I liked was when she referred to herself in her college years as “a little Bovarist” which points to Emma Bovary in the novel Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert. Emma Bovary was romantic and wanted to use a wealthy husband as a way to escape her boring life. But this is another seemingly counterintuitive inclusion, because Emma Bovary leaned too much on her romantic ideals and materialism. These behaviors led her to have multiple unfulfilling affairs. Her husband tried to make her happy, but she spent so much money that her marriage suffered debt and financial ruin, and she eventually swallowed arsenic and died a painful, self-inflicted death. So, if I were the editor, I would have some questions for this writer. I would ask, if you are arguing in favor of marrying an older, wealthier man, why are you referencing examples of fiction that seem to succinctly argue against you?

*big sigh*

Okay. Let’s talk about Lolita.

Christie mentions Lolita multiple times throughout this essay. She mentions working on a “Nabokov paper” in undergrad, Nabokov is the author of Lolita, she quotes the book, saying “You took advantage of my disadvantage,” and has another call back to that quote and this is a ~4,000 word essay, so she really wants us to get this reference.

Lolita, the book, has every right to exist, and we have every right to read it. Personally, I don’t believe in censoring fiction. Ultimately, if something exists and happens in the real world, then artists should have the freedom to reflect it in fiction and readers should have the opportunity to discuss it. That said, Lolita is a story about a middle-aged man who grooms and continually rapes his 12-year-old stepdaughter. She later escapes him only to be assaulted and impregnated by a different adult man when she is 17 and she dies in childbirth.

The writer of this essay, “The Case for Marrying an Older Man,” was 20 when she met her 30-year-old husband.

I would be very careful about referencing Lolita in an essay about a consensual, adult relationship, because, if we don’t do it well, it can sound like we’re saying that the author’s story, a girl in her 20s dating a guy in his 30s, is the same thing as pedophilia. Which it’s not.

I don’t know this writer’s personal life, but I have to wonder if her husband is comfortable with her publicly drawing a parallel between him and a famous pedophile. I don’t only feel that talking about Lolita in this context is disrespectful to her husband, but I also find it disrespectful to people who are survivors of grooming and pedophilia. So, if we are going to make a reference to Nabokov’s book, it should be gentle, deliberate, and well thought-out, but instead, the allusions to Lolita in this essay, similar to the other allusions in this piece, are often clunky and forced, so as an editor, I would probably delete them or strongly discourage the writer from including them.

Malapropisms

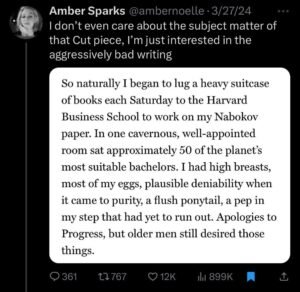

There is one specific paragraph that, well, if I were Christie’s editor, I would say, let’s stay off Twitter for a little while, girl, because they’re really roasting us for this paragraph. Let’s have a look.

She’s saying that she wants to use her beauty and youth to her advantage to marry into a life of luxury and she says:

“So naturally I began to lug a heavy suitcase of books each Saturday to the Harvard Business School to work on my Nabokov paper. In one cavernous, well-appointed room sat approximately 50 of the planet’s most suitable bachelors. I had high breasts, most of my eggs, plausible deniability when it came to purity, a flush ponytail, a pep in my step that had yet to run out. Apologies to Progress, but older men still desired those things.”

Again, we aren’t talking about content, so let’s look at the writing. The Nabokov paper thing, we already decided we’re gonna take that out. It will be an easy deletion because it does nothing to move the story forward except maybe to clarify that she was in the business library despite being an English student. which we could have clarified without mentioning Lolita again.

Here, we have a malapropism when she says she has a “flush ponytail.” A malapropism is when the writer uses a homophone, or, a word that sort of sounds like the correct word, but has a completely different meaning. These are most famously employed by Shakespeare. Remember when I said that grammar rules can be broken so long as the writer does so deliberately and in service of a greater intention? When Shakespeare uses malapropisms, they’re usually only in the dialogue of certain characters. He uses malapropisms for humor, silly miscommunications, or to show that a certain character is uneducated or intended for comic relief. In this essay, when she said a “flush” ponytail, I believe she meant either full or lush or maybe she combined those two words. I don’t like to blame the editor because we don’t know what state the essay was in when the editor got it, but it was probably their job to catch that one. Either way, it’s one word, honestly not a big deal.

Factual Errors

I am also seeing some factual errors. Women are born with a finite number of eggs, and they gradually deplete over time. This is different from men who continuously produce sperm, even though the quality of that sperm goes down as they age. So the most eggs you will ever have as a woman is when you are a young fetus. So unless this author was at 20 weeks gestation when she wrote this, the “most of my eggs” line is not accurate and we can take it out.

The Male Gaze

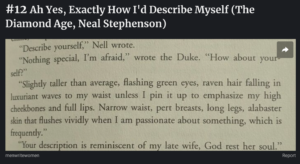

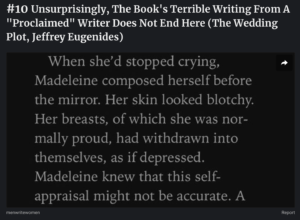

There’s a long-standing joke in the writing world about women written by men, and examples usually show cases of female characters being hyper-aware of their own breasts at all times, or describing themselves and their appearance in an overtly sexual way instead of like a human having a human experience. Here are some examples from an article by Bored Panda (full disclosure, I haven’t read any of these books so I could be taking quotes out of context; that’s entirely plausible):

(I just included this one because it sounds so similar to the paragraph from this essay.)

This writing is an example of the “male gaze” in literature, which was a concept coined by the film critic Laura Mulvey to refer to women characters being portrayed as objects of men’s desire instead of subjects themselves.

I do think that male writers get a lot of flack for this, which can be an issue because women can be very misogynistic in their writing, and we shouldn’t get a get of jail-free card for that just because we’re women. This essay, this paragraph, is a great example of a woman writing with the “male gaze.”

A good way to tell if you’re writing a character in a stereotypically gendered, male-gazey way could be to swap out the gender and see if the writing sounds silly. You might say, in this case, we can’t swap this out for a male character because men don’t have a biological clock, and this paragraph is about youthful fertility. But men do have a biological clock. With time, the quality of men’s sperm goes down and the chances of having a child with genetic or mental health disorders goes up with the father’s age. So let’s try this paragraph again, this time written about a youthful, fertile man:

“In one cavernous, well-appointed room sat approximately 50 of the planet’s most suitable bachelorettes. I had a high sperm count, a low hairline, a virginal gait, and a pep in my step that had yet to run out. Apologies to Tradition, but older women still desired those things.”

I’ll let you as the reader decide if we think a male audience would feel rightfully alienated by that writing.

The Parts I Liked

I’ve been harping on this writer for a while, but there are some things that I genuinely like about the essay. When her voice works, it works really well. There are some lines that I think are well-written, expressive, and artistic like these:

“The thought, when it descended on me, jolted my perspective, the way a falling leaf can make you look up.”

Beautiful.

“I went to him, asked him for a cigarette. A date, days later. A second one, where I discovered he was a person, potentially my favorite kind: funny, clear-eyed, brilliant, on intimate terms with the universe.”

My favorite parts are when she describes her husband with love and with vulnerability. In the last paragraph, she says:

“Once, when we first fell in love, I put my head in his lap on a long car ride; I remember his hands on my face, the sun, the twisting turns of a mountain road, surprising and not surprising us like our romance, and his voice, telling me that it was his biggest regret that I was so young, he feared he would lose me.”

That’s touching and it’s honest and I wish that she had leaned more into talking about the love she has for her husband instead of trying to sway the reader in a certain direction. By taking such a stubborn stance in this essay, she opened the door for people to comment saying that her husband is cheating on her and he will leave her for a younger woman when she gets older and all these other attacks that are cruel and unfair. It seems like she really loves her husband and if their relationship is healthy then I hope they stay together and continue to find success as a couple.

My Personal Take

Which brings me to this point: Is she a bad writer? I don’t think so.

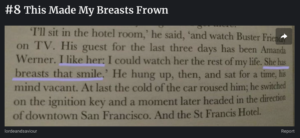

But her voice, in the opinion essay format comes across as immature and insecure, which readers typically don’t like in a personal opinion piece.

For example, writing: “I could study all I wanted, prove myself as exceptional as I liked, and still my fiercest advantage remained so universal it deflated my other plans. My youth. The newness of my face and body.”

Thinking that your greatest advantage is your body or age is very sad and unhealthy. If I were a friend of hers, I would be worried about her for writing this.

There are universal truths that come with being human, like the fact that we understand our own mortality, or the fact that we have this big, seemingly infinite, connected consciousness, and it’s strapped to this slowly expiring body as a vehicle; these are difficult facts to deal with and we carry them every day. A big part of maturity is coming to peace with these facts and learning to live with them. A sign of immaturity is coming to conclusions that make these universal truths feel worse and heavier; adding emotional baggage to them that is counterproductive.

She also writes: “I resented the callow boys in my class, who lusted after a particular, socially sanctioned type on campus: thin and sexless, emotionally detached and socially connected, the opposite of me.” She doesn’t see that she is being hypocritical here. She’s criticizing men her age who want a socially connected woman, but isn’t the point of the essay to say that women should be looking for socially connected men?

But sometimes, when I was reading, there were moments when I asked myself if the point of the essay was to argue in favor of marrying an older man or to brag about her own relationship and life, to herself, and to us. There are sections when she randomly inserts facts about herself that do nothing to prove her thesis or move the narrative forward. Like in this example:

“When a 50-year-old man and a 25-year-old woman walk down the street, the questions form themselves inside of you; they make you feel cynical and obscene: How good of a deal is that? Which party is getting the better one? Would I take it? He is older. Income rises with age, so we assume he has money, at least relative to her; at minimum, more connections and experience. She has supple skin. Energy. Sex. Maybe she gets a Birkin. Maybe he gets a baby long after his prime. The sight of their entwined hands throws a lucid light on the calculations each of us makes, in love, to varying degrees of denial. You could get married in the most romantic place in the world, like I did, and you would still have to sign a contract.”

That “like I did” comes out of nowhere and serves no purpose in the greater essay. The only reason I could see why she would include that detail is that she feels it paints her favorably. The essay is full of instances like these, which causes me to wonder how much she is trying to prove to us that marrying older was the right decision, and how much she is trying to convince herself.

And there are times when I genuinely worry about her emotional tenacity and mental health, like when she says: “Last week, we looked back at old photos and agreed we’d given each other our respective best years.” Thinking your best years are behind you sounds like a good way to put yourself on the depression fast track. It also sounds like a fallacy committed by a young person who thinks that her best attribute is her young body. Interestingly, bragging about yourself and your life often goes hand-in-hand with deep-set insecurity. Both are symptoms of an inflated ego.

However I can see the seeds of the more mature person that she’s becoming. There are sentences here and there when she recognizes the value and love in other people’s relationships, not just her own. “On occasion I meet a nice couple, who grew up together. They know each other with a fraternalism tender and alien to me.” That’s a necessary inclusion that I wish she had written more about.

I don’t think this writer should never write again; I would never encourage anyone to never write again because, although some of us would like to think about writing as some sort of elite, genius behavior, writing at its best is really a tool for catharsis and self-expression that should be available to everyone; it shouldn’t be gatekept. But this writer especially has a lot of potential to get better. In fact, I think that if she took this voice, these attributes that garnered criticism for this essay, and put them into a short story, assigning them to a character instead of to herself, then people might celebrate it. I mean, we celebrate the main character of “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” by Ottessa Moshfegh.

In fiction we don’t always have to worry about the characters being likable like we do sometimes with a personal brand. The same qualities that are frustrating here would seem, in fiction, like a statement about materialism or transactional relationships, “a baby for a Birkin,” and the writer and the reader could stand together and point at the character and laugh at them instead of the readers pointing at the writer and laughing at her while she stands alone.

This writer mentions in her Twitter bio that she’s writing a novel and I would encourage her to keep it up; don’t get discouraged by how this essay was received, I don’t think that many of the same criticisms would apply to your fiction if it’s done well. And by done well, I do mean that the character with these immature attributes will have to grow and experience a character arc. If they stay immature the whole story, it will seem like you’re endorsing immaturity.

Now, I don’t know this woman. I don’t know her husband. I’m not here to comment on their relationship and whether or not I think they’re getting a fair trade. I personally disagree with many of the author’s takes on relationships and feminism. But who cares? I’m not here to convince her of anything. I’m her editor, not her mother.

However, the personal decisions we make inevitably influence our work as writers and artists. The only part of the essay where the writer surprised me was when she revealed that she is 27. She’s almost the same age as me. Up until that point, I had thought I was reading something written by a precocious 19-year-old. And I realized that a lot of the mistakes that this writer made, like talking about her life in a way that comes across as boastful, thinking that a 21-year-old is “in her prime,” thinking that because something worked for her, it must work for everyone else, assuming that everyone who disagrees with you in just in denial, hitting us over the head with her references to classic literature, a lot of these errors are just… immaturity.

How to talk about your life in a positive way without sounding pretentious, how to speak about something you learned without sounding preachy, these are complex social skills that take a while to learn and a lot of people don’t really hone and develop them until their 20s. I wonder if this writer’s decision to marry into the life she wanted instead of building the life she wanted could have somewhat stunted her maturation.

It’s this concept of “choose your hard.” It’s hard to, I don’t know, eat nutritious food every day. But, well, it’s also hard to have health issues because you didn’t give your body proper nutrition. So. It’s gonna be hard either way. Just pick one.

And this writer… she’s right. It is hard to make money as a young woman in your 20s. It’s hard to establish a career as an artist without financial support. It’s hard to be in a relationship with someone who is equally as young and clueless as you. And it’s hard to sacrifice ease and comfort in exchange for discipline and personal growth. But… it’s also hard to forgo your own development as an artist and have your writing very publicly mocked and criticized for sounding like it was written by a teenager. Maybe it helps to be a young woman when you’re trying to get into a bar, but it usually doesn’t do much for you when you’re trying to make good art. It appears that this author may have tried to forgo something hard, and instead just exchanged it for something else hard.

Christie wrote: “I could diligently craft an ideal existence, over years and years of sleepless nights and industry. Or I could just marry it early.” And it sounds like a tempting prospect. But those “years and years of sleepless nights and industry” aren’t just the time that a woman spends amassing wealth or climbing a ladder. They’re the years that she is growing as a person. And you can’t marry into personal growth. The only way to build your sense of self and maturity is through facing challenges and overcoming them. That’s it. There’s no shortcut. In the words of Alex Hormozi: “No one is born with an iron will. We all come out crybabies.” After all, becoming a great artist doesn’t always have as much to do with talent as it does to do with grit. I’m reminded of a scene in the movie Whiplash, when Andrew Neiman, a young percussionist, says to his conductor and antagonist, Terence Fletcher about his excessive teaching methods, “But is there a line? You know, maybe you go too far and you discourage the next Charlie Parker from ever becoming Charlie Parker?” And Fletcher replies: “No. Because the next Charlie Parker would never be discouraged.”

My only recommendation to this writer is that she look at the criticism she is falling under and, instead of dismissing it, taking it as an opportunity to grow and become a better writer. I hope that this is only one small part of your künstlerroman, and that you come out on the other side better for it.

I also want to thank the writer of this piece for giving us something with so much to dissect and discuss; I’ve really enjoyed doing this breakdown.

I work for a small writing and editing business called Inkless. We do edits like this all the time so if you’re looking for an editor, please contact us; we’d love to learn more about your project.

_____________________________

Sign up for my newsletter to know when I publish new stuff: https://www.surveyhero.com/c/ck4sfziw

Contract writing or editing services: https://inklessagency.com/

Watch this blog post as a video essay: